Elementary Functions

Topology of Complex Space

Note that with the definition as \(a+bi\), the complex space can be seen as a \(\mathbb R^2\) space, and have all topology definitions defined as reals.

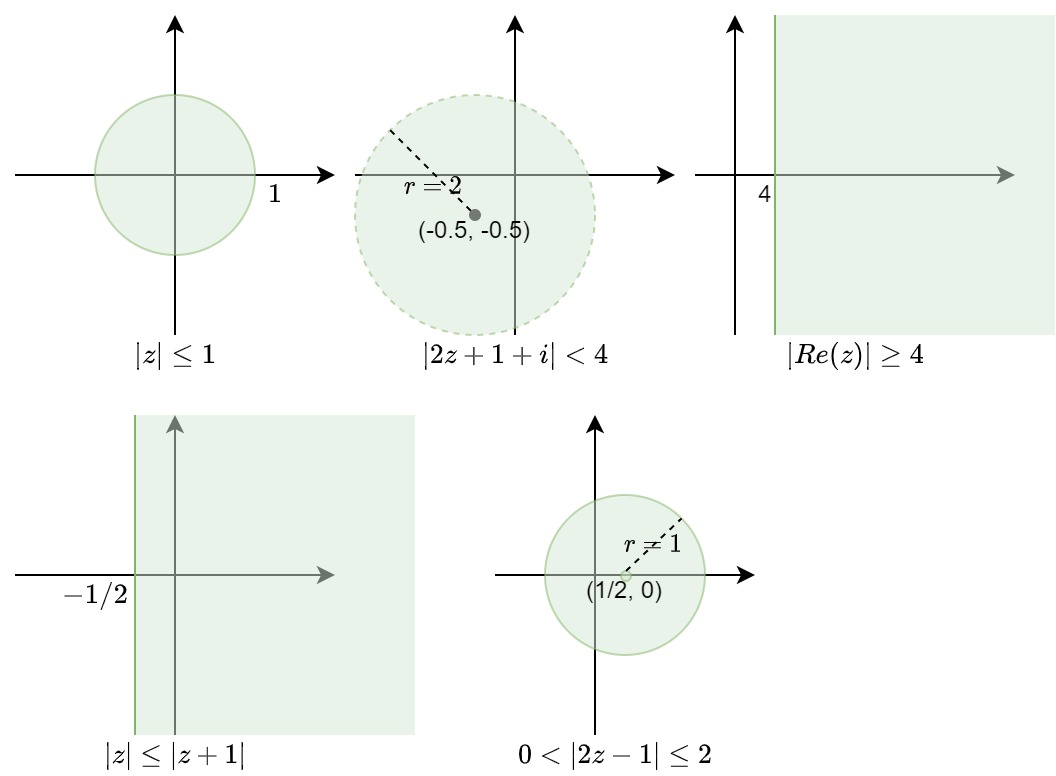

Example 1

- \(|z|\leq 1\) not open, closed, bounded, compact

- \(|2z+1+i| < 4\) open, not closed, bounded

- \(Re(z) \geq 4\) not open, closed, unbounded

- \(|z| \leq |z + 1|\) not open, closed, unbounded

- \(0 < |2z-1|\leq 2\) not open, not closed, bounded

Example 2

determine connectedness and the closure

\(0 < \arg z \leq \pi\) not connected, \(\bar S = \{z=x+iy: x=0\lor y =0\} = \{z = re^{i\theta}:\theta = 0 + 2n\pi\lor \theta = \pi + 2n\pi\}\)

\(0 \leq \arg z < 2\pi\) connected, \(\bar S = \emptyset\)

\(Re(z) >0\land Im(z) > 0\) connected, \(\bar S = \{z=x+iy: (x=0\land y \geq 0)\lor (y=0\land x\geq 0)\} = \{z=re^{i\theta}: r \geq 0\land (\theta=0\lor\theta = \pi)\}\)

\(Re(z-z_0) > 0\land Re(z-z_1) < 0, z_0,z_1 \in \mathbb C\). If \(Re(z_0) \leq Re(z_1)\), then connected, otherwise unconnected.\(\bar S = \{z:Re(z) = Re(z_0)\lor Re(z) = Re(z_1)\}\)

\(|z| < 1/2 \land |2z-4| < 2\) note this is \(\emptyset\), hence connected and closure is \(\emptyset\)

Elementary Functions

A function of the complex variable is some function that maps to a subset of \(\mathbb C\).

Define polynomials of degree \(n\) as \(P_n(z) = \sum^n_0 a_iz^i\).

Define rational as a ratio of two polynomials, given the quotient is not \(0\).

Generally, a complex function can be written as \(f(z) = u(x, y) + iv(x, y)\), i.e. the real part and the imaginary part.

Example 1

For the transformation \(w=z+1/z=u+iv\), show that \(\forall z\in\mathbb C. (Im(z) > 0\land |z| > 1)\Rightarrow \exists v > 0\).

proof.

so we have \(u = x + \frac{x}{x^2+y^2}, v = y - \frac{y}{x^2+y^2}\), since \(x^2 + y^2 > 1, y > 0\), \(v>0\)

Exponential functions

Define the sum of exponent as

Noting that this equation plus trigonometric identities imply that

Trigonometric functions

Define the trigonometric functions on complex numbers as

Then, other trigonometric functions are taken from this definition.

Define the hyperbolic functions as

The usual trigonometric identities hold on these definitions

It's worth noting that

Example 2

Prove angle sum identities using complex numbers. proof For \(a,b\in\mathbb R\),

Power Series

Define a power series of \(f(z)\) about the point \(z=z_0\) as

Ratio test (motivated by reals) also holds on complex numbers even though we won't prove it here: If \(\lim_\infty \lvert \frac{a_{n+1}}{a_n}\rvert |z - z_0| < 1\), then the power series converges, and the radius of convergence is

\(R=\infty\), then the series converges for all finite \(z\), \(R = 0\), then the series converges only for \(z=z_0\).

Some common power series representations:

We will prove \(e^z = \sum \frac{z^j}{j!}\) from Euler's formula and series expansion from reals

Using the series above, we can then derive for \(\sin z\) as

Stereographic Projection

Consider a unit sphere sitting on top of the complex plane with the south pole of the sphere located at the origin of the z plane. Connect the point \(z\) in the plane with the north pole using a straight line. This line intersects the sphere at the point \(P\). In this way each point \(z= x +i y\) on the complex plane corresponds uniquely to a point \(P\) on the surface of the sphere. This construction is called stereographic projection. The extended complex plane is sometimes referred as the compactified (closed) complex plane.

Consider the 3 points \(N = (0, 0, 2)\) is the north pole of the ball, \(P=(X,Y,Z)\) be the points on the sphere, and \(C = (x, y, 0)\) be on the complex plane. Since they are on the same line, we have

and note that \(P\) is on the sphere so that \(X^2 + Y^2 + (Z-1)^2 = 1\).

Now we have 4 unknowns \(X,Y,Z,s\) and 4 equations, and it solves to be

Similarly, if we have \(X,Y,Z\), we can solve to have

Note that \(P=(0, 0, 0)\) maps to \(z=0\) and \(\lim_{|z|\rightarrow\infty}(X = \frac{4x}{|z|^2 + 4}, Y = \frac{4y}{|z|^2 + 4}, Z= \frac{2|z|^2}{|z|^2 + 4}) = (0, 0, 2)\) (all \(z\) with \(|z|=\infty\) maps to the north pole). Any bounded region on the complex plane can be projected on the sphere, and any region, excluding the north pole, can be mapped to the complex plane.

Example Consider the line \(Re z = x = 0\), the projected line on the sphere is